Table of Contents:

The Yoneda Lemma, a cornerstone of Category Theory, posits that the essence of a mathematical object is not in the object itself but in its relationships with other objects. In formal terms, an object in a category is fully determined by the morphisms (arrows) it has with other objects. This lemma serves as a foundational concept in the "mathematics of mathematics," offering a rigorous framework for understanding mathematical structures in terms of their relationships. For a deeper dive into the Yoneda Lemma and Category Theory, one may refer to nLab or Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

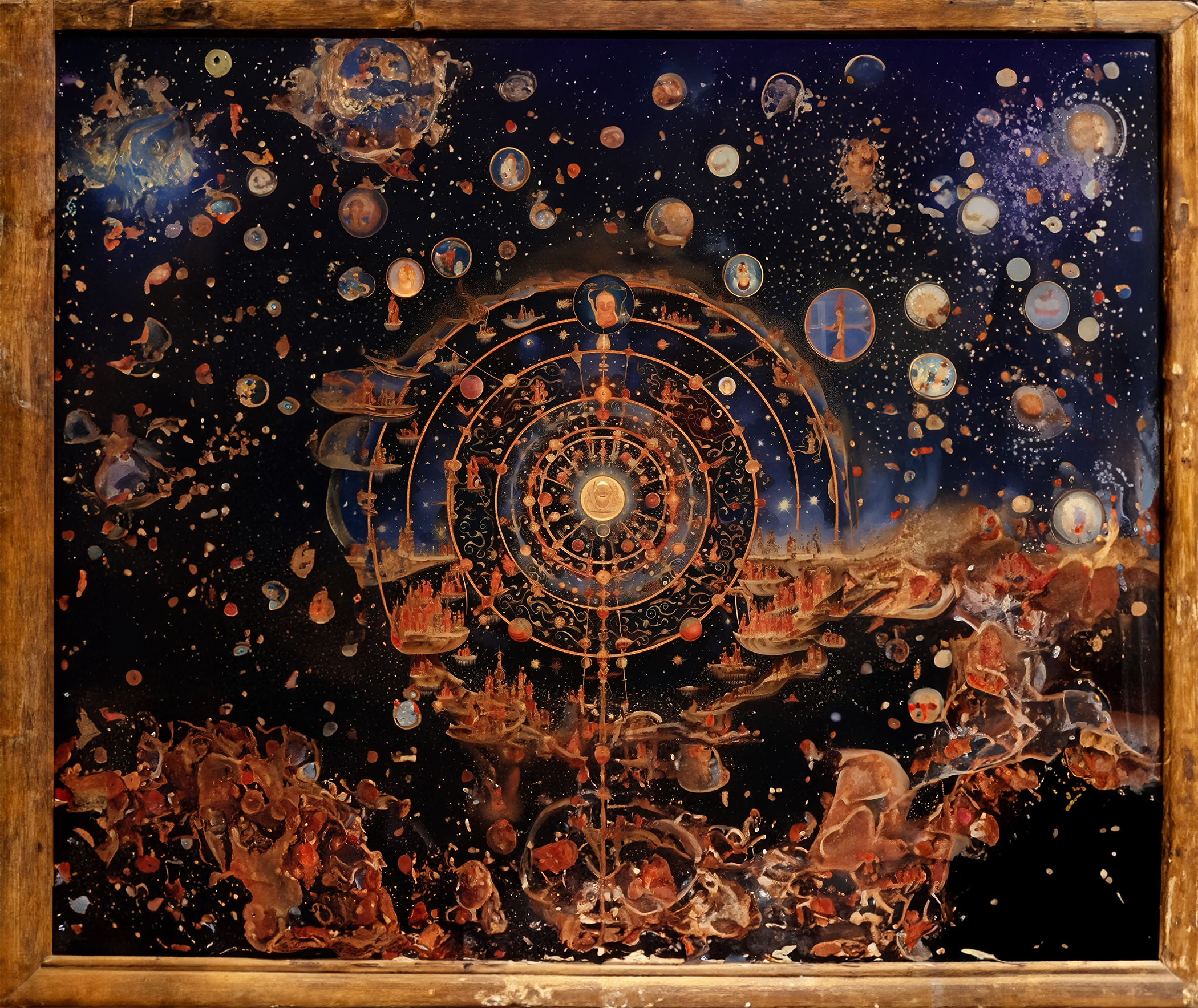

The Jeweled Net of Indra, a concept from Mahayana Buddhism, posits that each jewel in an infinite net reflects all other jewels. The essence of each jewel is not in its individuality but in its unique configuration of reflections of all other jewels. This metaphor is often cited in various sutras, including the Vimalakirti Sutra, which mentions the Parasol of the Goddess as another metaphor for interconnectedness. The Jeweled Net serves as a powerful metaphor for Sunyata (emptiness of nature), emphasizing that all dharmas are empty of inherent existence.

Moreover, the Jeweled Net suggests that each point of consciousness is the universe experiencing itself from that unique vantage point. The "Now" moment for each individual is a unique configuration in the net, reflecting and being reflected by all others. In essence, each subjective experience of consciousness is the universe itself, experiencing from a unique "Now."

Understanding the Yoneda Lemma involves a shift in perception. Mathematical objects are not static entities but dynamic nodes in a network of relationships.

This shift has parallels in subjective experience, where each moment can be seen as a unique configuration of sensory inputs, thoughts, and emotions. The three-world model—Subjective, Corporeal, and Objective worlds—offers a framework for understanding this. The Subjective world is the realm of individual experience, the Corporeal world is the realm of entities encountered through the senses, and the Objective world contains models of the Corporeal world.

The Jeweled Net of Indra provides a framework for understanding the interconnectedness of all points of consciousness. Each individual's experience of "Now" is a unique reflection of the entire universe. This aligns with certain interpretations of quantum mechanics and theories of consciousness that suggest that each point of observation is an intersection of Now to manifest uniquely complete in its actualization.

Both the Yoneda Lemma and the Jeweled Net emphasize that the essence of an object or an experience is in its unique set of relationships with everything else. Both frameworks suggest that the whole is reflected in each part. The Yoneda Lemma shows that an object is a set of relationships within the whole category. The Jeweled Net suggests that each individual's moment of "Now" is the universe experiencing itself.

The Yoneda Lemma and the Jeweled Net of Indra, though originating from disparate fields, converge on the idea that the essence of an object or an experience is fundamentally relational. While the Yoneda Lemma provides a formal way to understand this in the context of mathematical objects, the Jeweled Net of Indra offers a more poetic but equally profound understanding of this concept in the realm of existence and consciousness. Both serve as powerful tools for understanding the complex interplay between the individual and the universal, between the part and the whole.

While the Jeweled Net of Indra originates from Buddhist texts, its scope essentially lies in the realm of philosophy rather than religion. Buddhism is agnostic on the question of God, and the Buddha is considered a human who attained enlightenment. The Jeweled Net serves as a philosophical tool for understanding interconnectedness and contextuality, enriching the narrative of existence.

Phenomenology allows for the incorporation of both Buddhist philosophy and Category Theory into a scientific framework. It serves as the "science of sciences," providing a foundation through the recognition of distinctions between the Physical (Corporeal) world of measurements, the Subjective world of conscious experience, and the Objective World of shared language forms inscribed or interpreted from the experienced Physical (Corporeal, Lifeworld).

The term "witness" better captures the role of the subjective observer in experience. This aligns with the Catuskoti, a fourfold negation in Buddhist logic that challenges binary oppositions and the fixed nature of meaning. The witness undergoes a three-phase process: experiencing the lessons and reacting to them. Each phase can be seen through the lens of the Catuskoti, offering a nuanced understanding of subjective experience.

By exploring these frameworks and their intersections, one gains tools for understanding the complex interplay between individual and universal experiences, enriching both the scientific and philosophical narratives.

The Yoneda Lemma is a foundational result in category theory, a branch of mathematics that serves as a unifying framework for various mathematical structures and concepts. Category theory abstracts mathematical objects and the morphisms between them into categories, providing a language to discuss mathematical structures in a generalized way. The Yoneda Lemma, named after Nobuo Yoneda, formalizes the idea that an object in a category is determined by its relationships with other objects.

The Lemma states that for any category C and any object A in C, the set of morphisms from A to any object B in C uniquely determines A. In essence, you are what your relationships to other objects say you are. This result has profound implications, not just in pure mathematics but also in computer science, logic, and even philosophy, where it can be seen as a formalization of contextuality and relationality.

The Yoneda Lemma serves as a "mathematics of mathematics" in that it provides a meta-level understanding of mathematical structures. It allows mathematicians to understand categories (and thus, many mathematical theories) from the inside, based on how objects within those categories relate to each other.

For further reading:

The concept of Indra's Net originates from the ancient Indian text, the Atharva Veda, and has been elaborated upon in various Mahayana Buddhist sutras. It is often cited as a metaphor for the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things. The net is said to be a vast, cosmic lattice with a jewel at each vertex, and each jewel reflects all the other jewels in the net. This serves as a metaphor for the concept of "emptiness" (Sunyata), which posits that all phenomena (dharmas) are empty of inherent nature and exist only in relation to other phenomena.

The Parasol of the Goddess from the Vimalakirti Sutra can be seen as another metaphor that complements the idea of the Jeweled Net. The parasol symbolizes protection and sovereignty and is often used to represent the encompassing sky, under which all dualities and distinctions collapse. This aligns well with the concept of Sunyata, emphasizing that all dharmas are empty of nature, devoid of independent existence.

For further reading:

Both the Yoneda Lemma and the Jeweled Net of Indra serve as tools for understanding the relational aspects of their respective domains—mathematics and philosophy. They offer frameworks for understanding entities in terms of their relationships rather than as isolated objects, thereby enriching the narrative of interconnectedness and contextuality.

The Yoneda Lemma and the Jeweled Net of Indra are seemingly disparate concepts originating from the fields of mathematics and Eastern philosophy, respectively. However, both serve as profound tools for understanding the relational aspects of their domains. This article aims to delve deeper into these frameworks, emphasizing their role in enriching the narrative of interconnectedness and contextuality.

As previously discussed, the Yoneda Lemma in category theory posits that an object is fully determined by its relationships with other objects. This lemma has far-reaching implications, extending beyond pure mathematics to influence fields like computer science, logic, and even philosophy. It serves as a "mathematics of mathematics," providing a meta-level understanding of mathematical structures based on relationality.

The Jeweled Net of Indra, often associated with Mahayana Buddhism, serves as a metaphor for the interconnectedness and interdependence of all phenomena. Each jewel in the net reflects all other jewels, emphasizing that entities are not isolated but exist in a complex web of relationships. While the concept is rooted in Buddhist texts, its scope essentially falls under philosophy rather than religion.

Buddhism, particularly in its Mahayana form, is agnostic about the concept of God. While it does refer to gods and goddesses, these are considered beings within the Buddhafields or the multiverse, rather than supreme beings. The Buddha is viewed as a human who attained enlightenment, free from delusion. This focus on human potential and the nature of existence aligns more closely with philosophy's quest for understanding rather than religion's focus on divinity.

Both the Yoneda Lemma and the Jeweled Net of Indra emphasize that the essence of an entity—be it a mathematical object or a point of consciousness—is defined by its relationships. This shared focus on interconnectedness provides a unified lens through which to view and understand disparate fields.

Both frameworks suggest that the whole is reflected in each part. In the Yoneda Lemma, an object is a unique set of relationships within the whole category. Similarly, the Jeweled Net proposes that each individual's moment of "Now" is the universe experiencing itself. This idea aligns with certain interpretations of quantum mechanics and theories of consciousness, suggesting a complex interplay between the individual and the universal, between the part and the whole.

The Yoneda Lemma and the Jeweled Net of Indra, though originating from different fields, converge on the idea that the essence of an entity or experience is fundamentally relational. While the Yoneda Lemma provides a formal way to understand this in the context of mathematical objects, the Jeweled Net offers a more poetic but equally profound understanding in the realm of existence and consciousness. Both serve as powerful tools for understanding the complex interplay between the individual and the universal, enriching the narrative of interconnectedness and contextuality.

Phenomenology, Category Theory, and Buddhist Philosophy are three seemingly disparate fields. However, when viewed through the lens of relationality and interconnectedness, they offer a unified framework for understanding the nature of existence, consciousness, and mathematical objects. This article aims to explore these connections, drawing upon previous discussions on phenomenology and the "Three Worlds of Being"—the Corporeal, the Subjective, and the Objective.

Phenomenology, often attributed to Edmund Husserl, serves as a foundational pillar for understanding the first principles of various sciences. It provides a systematic way of synthesizing and integrating observations and predictions across phenomena. Phenomenology is often referred to as the "Science of Sciences" due to its meta-level understanding of various scientific disciplines. It serves as a bridge between the subjective world of conscious experience and the objective world of scientific inquiry.

Category Theory, featuring key concepts like the Yoneda Lemma, serves as a "mathematics of mathematics," offering a meta-level understanding of mathematical structures. The Yoneda Lemma posits that a mathematical object is fully determined by its relationships with other objects, emphasizing the importance of relationality in understanding mathematical structures.

Buddhist Philosophy, particularly the concept of the Jeweled Net of Indra, offers a framework for understanding the interconnectedness and interdependence of all phenomena. While often associated with religious contexts, the essence of these concepts is philosophical. Buddhism is agnostic about the concept of God and focuses on human potential and the nature of existence, aligning more closely with philosophy's quest for understanding.

The Corporeal world is the physical, tangible world that can be measured and observed. The Subjective world is the internal, mental world of thoughts, emotions, and experiences. The Objective world is the world of shared knowledge, language, and cultural constructs. These three worlds interact with each other, shaping our understanding of reality. Language and writing play a crucial role in shaping the Objective world, sometimes obscuring the direct experience of the Corporeal and Subjective worlds.

Essence in Relation: Phenomenology, Category Theory, and Buddhist Philosophy all emphasize that the essence of an object or an experience is in its unique set of relationships with everything else.

Universe in the Individual: All three frameworks suggest that the whole is reflected in each part. Phenomenology provides a methodological approach to explore this, Category Theory offers a mathematical formalism, and Buddhist Philosophy provides a more poetic but equally profound understanding.

Subjective Experience as Universal: In all three frameworks, the subjective experience is a point where the individual and the universal meet. Phenomenology offers a rigorous methodology for exploring this intersection, Category Theory provides the mathematical tools, and Buddhist Philosophy offers the conceptual framework.

Phenomenology, Category Theory, and Buddhist Philosophy, though originating from different fields, converge on the idea that the essence of an entity or experience is fundamentally relational. They serve as tools for understanding the complex interplay between the individual and the universal, enriching the narrative of interconnectedness and contextuality. Through the lens of these frameworks, one can better understand the intricate tapestry that constitutes our understanding of reality, from mathematical objects to conscious experiences.

The concept of the "subjective observer" has long been a point of discussion in both scientific and philosophical circles. However, the term "witness" offers a more nuanced understanding of this role, especially when considered in the context of Buddhist philosophy and the Catuskoti. This article delves into the three-phase process that the witness undergoes—experiencing, learning lessons, and reacting—and explores how each phase can be understood through the lens of the Catuskoti, a fourfold negation in Buddhist logic.

The term "observer" often implies a detached entity, merely recording events without active engagement. In contrast, a "witness" is not just an observer but an integral part of the experience. The witness is both the experiencer and the one who gives testimony to the experience, thereby adding a layer of reflexivity. This reflexivity is crucial for understanding the depth and complexity of subjective experience.

The Catuskoti is a fourfold negation used in Buddhist logic to challenge binary oppositions and the fixed nature of meaning. Also referred to as the Tetralemma, it consists of four logical possibilities: something is, is not, both is and is not, or neither is nor is not. This framework allows for a more nuanced understanding of phenomena, breaking free from the limitations of binary logic. It serves as a useful tool for examining the complexities of the witness's experience.

In the first phase, the witness is fully immersed in the experience. Whether it's a sensory perception, an emotional state, or a cognitive process, the witness is the locus where these phenomena manifest. Through the lens of the Catuskoti, this experience is not just a binary event of happening or not happening. It can exist in a state of ambiguity, being both present and absent in different aspects, thereby enriching our understanding of what it means to "experience."

The second phase involves the extraction of lessons from the experience. These lessons are not mere data points but integrated understandings that shape future experiences and reactions. Again, the Catuskoti offers a nuanced view. A lesson learned is not just a fixed piece of wisdom but a dynamic understanding that can be both true and not true depending on the context.

The third phase is the reaction, where the witness responds to the experience and the lessons learned. This is not a mechanical response but a complex interplay of various factors, including past experiences, current context, and future implications. The Catuskoti allows for a multifaceted understanding of this reaction, acknowledging that it can be both appropriate and inappropriate, both meaningful and meaningless, depending on various factors.

The concept of the witness, when examined through the lens of the Catuskoti, offers a rich framework for understanding subjective experience. It acknowledges the complexity and nuance inherent in each phase of the process—experiencing, learning lessons, and reacting. By moving beyond binary logic and fixed meanings, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a witness to our own lives, thereby enriching both scientific and philosophical narratives.